- Details

New ideas, new ways? The word is so frequently used in healthcare, and I am interested in exactly what it means. What do you think "innovation" means?

In health, innovation is usually linked to desirable and practical improvements in the consumer experience and outputs of care. I argue that innovation needs the consumer at the centre of idea generation, implementation and adoption. The consumer outcome is the WHY? of healthcare.

Do we really know what consumers want and prioritise in healthcare, and do we support ways of finding out?

For me this continues to drive my work. We know that walking the talk with the consumer at the centre creates much better innovation. From starting up Chronic Pain Australia in the early 2000's through to the recent citizens' juries I ran in Western Sydney. The juries were informed by the evidence and delivered something rarely seen - the juries delivered the well informed views of a representative sample of WS population - the health and social care priorities of people in WS. Working with WS people has been one of the major highlights of my career. Importantly, the lens is "for the public good".

Not surprising to me was that the people want preventative healthcare that is relationship-based, that keeps families together for the health and wellbeing of this and future generations. The community wants accessible and effective preventative health care. Now that we know, how do we provide that care? The community needs organisations that are ready to listen and support these priorities in culturally respectful ways.

And this, in my world, is innovation. The irony is that the identified priorities are what humans have wanted forever. It is the relationship that defines us. Being healthy and well to be able to respond to and care for our loved ones - and others in the community that we don't even know. We are defined by kindness and compassion and it is what makes us the species we are on planet Earth.

Now that the Jury project has come to an end, I am looking forward to working on new projects and with new organisations that put the consumer at the centre. I love working in the community.

Tell me what you think "innovation" means. Let's get on with it.

- Details

I remember during my training there was a discussion about whether a “manager” could manage clinicians. I heard the debate and we never seemed to land. My gut was that an MBA didn’t help you understand the complex human landscape involving existential crises, fear, skill, relationship and courage - among other human experiences - the business-as-usual environment for highly skilled health professionals - doctors, nurses, counsellors, social workers and a long list).

When you look at the literature about managerialism the common message is that it is a system where all decisions are made not by those with the expertise (nurses, doctors and other health professionals), but by those who have management training (see for example Klikauer, Thomas. Managerialism a Critique of an Ideology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) It is pervasive. It is common throughout education, health and other public services. Its throughout politics.

I don't think we, the people, really even know this is happening. I think it is behind so many of the stories I have heard for decades from patients who talk about an immutable decision that affected their family member. Some involve losing their loved one. I think managerialism is behind all of it.

I know it’s hard, but I believe we need to hold hands and reclaim our power to make collective decisions that work towards a better system. My subjective sense is that more and more of us are starting to grow our awareness of how this ideological outcome is reducing our sense of our decision makers working towards "the public good."

The citizen juries hosted by Wentwest that we ran in Western Sydney in 2023 aimed to bring well-informed citizens into a new awareness of how our systems spend our money and what the alternatives were. Yes we can! The image is a summary of what the people recommended at the end of the first of two citizen juries in Western Sydney when asked the question "should we, the people of Western Sydney, continue to invest in health in the same way as we have in the past?"

- Details

The First Nations population is growing, but in many ways so are the inequities. We need to find pathways to nurture young First Nations people into health and social care education pathways in Australia. Professor Kong is an exemplar for what happens when we find such a pathway. Our challenge is to find ways to upscale these moves.

I read an article recently about the importance of Indigenous Scholarships in the systematic development of First Nations individuals to become leaders in improving the health outcomes for all people.

Professor Kelvin Kong is a hero of mine. As Australia's first Indigenous Ear, Nose and Throat specialist surgeon he is tackling one of the most widespread problems for First Nations people - lack of access to specialist care to ensure kids can hear well, learn well and thrive.

"Australia’s first Indigenous surgeon has urged more organisations to show their support for initiatives that help improve health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Professor Kelvin Kong, the 2023 NAIDOC Person of the Year, highlighted the importance of programs like the AMA’s Indigenous Medical Scholarship.

Professor Kong was one of the first scholarship recipients in 1997 and said not only did it provide crucial financial assistance during his medical studies at the University of NSW, it also provided significant personal motivation to push himself forward.

“When I was growing up, medicine was not even an option to anyone in our family. You were lucky enough to get through schooling, let alone think about university,” he said.

“The scholarship was a reminder for me that I deserved to be in that place, and to have that kind of support and encouragement was really important, as it enabled me to dream big.”

Professor Kong, a Worimi man, said receiving the scholarship also made him realise the importance of organisations such as the AMA showing leadership and driving change.

“People probably don’t realise the far-reaching consequences of the support of the AMA and their members in this space,” he said.

“Some people think that simply speaking up in support of First Nations Australians won’t do anything, when in actual fact, simply saying ‘this is something we believe in and this is something that’s important to us makes a huge difference.”

Professor Kong now works as one of the country’s foremost head and neck surgeons and has dedicated his career to the treatment and early intervention of chronic otitis media, which disproportionately affects Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children". READ MORE HERE

- Details

Since I started out in the world as a new grad, I have witnessed significant changes in the way our world works. I noticed the shift from a government-run organisation to support people with disabilities, however acquired, to a privatised system where perverse incentives motivated the approach to people with disabilities. The 20th century had seen wars and great social disruption, and what had been a post-war effort to bring our society together safely and respectfully, was eroded by a push towards neo-liberal values around market forces. There are benefits in that, and also costs.

Since I started out in the world as a new grad, I have witnessed significant changes in the way our world works. I noticed the shift from a government-run organisation to support people with disabilities, however acquired, to a privatised system where perverse incentives motivated the approach to people with disabilities. The 20th century had seen wars and great social disruption, and what had been a post-war effort to bring our society together safely and respectfully, was eroded by a push towards neo-liberal values around market forces. There are benefits in that, and also costs.

In my morning walk/think time I stumbled across an interesting and provocative podcast about the social contract:

https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/futuretense/building-a-new-social-contract-/103022958

"There’s a growing public sense that the current model of the social contract is broken, due in large part to rising inequality and the pursuit of profit over social progress.

The “social contract” defines the relationship between citizens, their government and business. Its modern form emerged after WWII and, in western democracies, was largely structured around the principles of the welfare state. It’s about equity, order and trust.

So, does the essence of the social contract still have value? And if so, how can it make fit for purpose in the 21st century?"

- Details

My work is guided by these principles. See Principles-focused evaluation by Michael Quinn Patton for more, also the resources page which embodies the principles below.

My work is guided by these principles. See Principles-focused evaluation by Michael Quinn Patton for more, also the resources page which embodies the principles below.

- We create a co-design environment

- We create space for the people affected in any decision about their world to lead by their experiences

- We trust well-informed community decision-making

- We take responsibility for providing high quality information in ways that can be understood - We promote health literacy

- We take the time to build the relationship - We work together by accommodating each other’s objectives to build our relationships into partnerships – we are reciprocal.

- We strengthen the voice of the consumer – we understand the confidence value in numbers.

- We always close the loop – we understand the importance of transparency and commitment to outcomes in partnership building.

- We go slow to go fast – We build on our strengths and prepare to be ready for opportunities.

- We think systematically – we find the system in the complexity and don’t reinvent wheels.

- We look for opportunities to realise multiple benefits with one intervention.

- Details

Primary Health Networks are mandated to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of health services for people, particularly those at risk of poor health outcomes. They are also mandated to improve the coordination of health services, and increase access and quality support for people in their local region [1].

The challenge is that to make serious improvements in population level health outcomes, deliberate attention needs to be paid to the social determinants of health. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), these are:

The challenge is that to make serious improvements in population level health outcomes, deliberate attention needs to be paid to the social determinants of health. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), these are:

“ … the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life … the lower the socioeconomic position, the worse the health” [2].

It is tempting to say "but we are not able to deliver social care, we are a health services provider". My question is, can we get creative and innovative to achieve the mandate?

Can we hold hands with social care providers and the community to solve this challenge?

I believe we can. There are good examples of how we can do this [3]. System change will occur, when we, those on the ground and holding the potential for change, influence funders through the hard-to-resist argument that when we do connect up health and social, the return on investment is substantially better than current ways of funding and delivery of services.

And here is the opportunity: in connecting up both health and social care, Primary Health Networks are able to deliver what communities have always wanted - non-siloed, cost-effective, co-designed and safe services that keep people well, healthy and out of hospitals.

References

1. Australian Government. What Primary Health Networks are. 2021 [cited 2023 13 January]; Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/phn/what-PHNs-are.

2. World Health Organisation. Social determinants of health. 2023; Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

3. National Academies of Sciences, E. and Medicine, Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation's health. 2019.

- Details

Just in time for the 2022-23 summer Tim Dunlop delivered a great new book. I couldn't put it down.

Just in time for the 2022-23 summer Tim Dunlop delivered a great new book. I couldn't put it down.

His point is that the standard two party political system in Australia - and more broadly across Western countries - is letting us down. Its about trust. Increasingly the people don't trust politicians and Dunlop takes us through his thinking about why. I'm interested in the methodology used by a large number of Independents over the last few years. The "kitchen table" conversations are the basis for hearing what matters to community members. Yes, listening, and responding.

He says:

The challenge that remains for all of us who support the democratic advances made on 21 May (2022) is to invest the institute\ions of the state with the same processes of engagement and co-operation. To do that, we need to understand the origins and power of the Voices Of methodology.

I couldn't help agreeing. What we do in our daily work in the community is all about listening to what communities tell us, but importantly being faithful in responding to that voice authentically.

If you want to hear more, here is an article and podcast: https://nofibs.com.au/podcast-tim-dunlop-talks-about-his-independentsday-book-voices-of-us/

- Details

In healthcare we are good at rescuing people after they have become ill. But what if we took more notice of the things that make us sick in the first place? These are the "upstream factors". In fact we invest a lot in rescue care, but only 1% of that is to prevent us getting sick.

Rishi Manchanda has worked as a doctor in South Central Los Angeles for a decade, where he’s come to realize: His job isn’t just about treating a patient’s symptoms, but about getting to the root cause of what is making them ill—the “upstream" factors like a poor diet, a stressful job, a lack of fresh air. It’s a powerful call for doctors to pay attention to a patient's life outside the exam room.

- Details

"Medicare no longer works, for patients or GPs.

The way GPs work and get paid should be overhauled so Australia can turn the tide of chronic disease, keep more people out of hospital, and ensure poorer Australians get the care they need when they need it.

Australia’s universal healthcare system has failed to keep up with changes to Australians’ health needs since it started four decades ago.

GPs’ work has become much more complex, as the population has grown older and rates of mental ill-health and chronic disease have climbed. But the way we structure and fund general practice hasn’t kept up.

Despite patient care becoming more complex, appointments have been stuck at an average length of 15 minutes for the past two decades. GPs are struggling to meet their patients’ needs, and they lack the support of a broader team of health professionals to do so.

Other countries have reformed general practice, and their rates of avoidable hospital visits for chronic disease are falling. But Australia is spending more on hospitals while neglecting general practice: the best place to tackle chronic disease.

Patients suffer the consequences. People with chronic disease live shorter lives, with more years of ill-health, and lower earnings. Poorer Australians suffer the most: they are twice as likely to have multiple chronic diseases as wealthy Australians.

Australia’s healthcare workers are also struggling. Hospital staff are overwhelmed with demand. And GPs tell us they are stressed, disrespected, and disillusioned.

To bring Medicare into the 21st Century, the report recommends big changes.

First, general practice needs to become a team sport, with many clinicians working under the leadership of a GP to provide more and better care.

To achieve this, the federal government will have to dismantle the regulatory and funding barriers that force GPs to go it alone. To accelerate the change, 1,000 more clinicians, such as nurses and physiotherapists, should be employed in general practices in the communities that need them most.

Second, Australia needs to change the way GPs are paid. The current method is broken – it actively discourages GPs from working with teams, and it rewards GPs who see lots of patients in quick succession, rather than spending more time with patients who need more care.

GPs should be able to choose a new funding model that supports team care and enables them to spend more time on complex cases, by combining appointment fees with a flexible budget for each patient based on their level of need.

Third, Australia must give clinics the data, funding, and support they need to give the best possible care to their patients.

Medicare is in the grip of a mid-life crisis. The reforms we propose will give more patients better care, and boost GPs’ job satisfaction.

And our reform plan is affordable. The Albanese Government has set aside $250 million a year to fix Medicare. That money can fund the recommendations in this report, repairing the foundation of Australia’s healthcare system and creating a new Medicare that is ready for the decades ahead"

- Details

Michael Quinn Patton is a hero of mine. In the early 2000's I read a book called 'Getting to Maybe: how the world is changed'. Patton was one of three authors. If you are interested in learning from successful social innovation initiatives from around the world, this book is an eye-opener.

Michael Quinn Patton is a hero of mine. In the early 2000's I read a book called 'Getting to Maybe: how the world is changed'. Patton was one of three authors. If you are interested in learning from successful social innovation initiatives from around the world, this book is an eye-opener.

He has been developing his approach to dealing with complex human systems since way back in the 70's and 80's - and this has led him to current thinking about evaluation. I find the approach is very useful. It can provide a framework not only for evaluation but also for how you proceed with your work, how you decide what needs to happen next.

- Details

How many times have I heard this objection? You are a manager delivering health / social care services. You put out an expression of interest to recruit a number of community members to be a part of your group - your "council" or "panel". This group will most likely - if facilitated well - provide good input during discussions of the various health topics.

How many times have I heard this objection? You are a manager delivering health / social care services. You put out an expression of interest to recruit a number of community members to be a part of your group - your "council" or "panel". This group will most likely - if facilitated well - provide good input during discussions of the various health topics.

I have had some wonderful experiences with Consumer Councils. They are usually made up of extraordinary people who have a passion for volunteering and getting involved in health improvement activities and can really make a difference. Unfortunately, in some bureaucracies, what that group recommends may not be what the bureacracies want to hear. It is not uncommon to hear the criticism "But it's not representative!"

And mostly it's not. This becomes a way of shutting down or ignoring the outcomes from discussions of your Council.

One way of ensuring "representativeness" is through Deliberative Democracy. One application is the "Citizen Jury" methodology. A random sample is selected from a population of interest then stratified to ensure the sample does reflect the population profile. It's representative.

What is even more powerful is if this Citizen Jury becomes a permanent "Citizen Assembly". Permanency is important because it gives the local population enough time to develop trust in this powerful way of tapping into local well-informed intelligence.

One-off citizen juries can be amazing for everyone. However, they often have little impact on policy or decisions more broadly. For example, despite a one-off citizen jury in Ontario in 2007 making a well-considered recommendation that the voting system should change, a referendum for change later that year failed. Subsequent analysis found that:

“This experience underlines a major drawback of ad hoc assemblies. They do not have enough time – enough history – to generate broad understanding of their role and purpose, hence their recommendations lack the power and influence we might expect of permanent institutions” [1].

However, in Europe there is a permanent assembly linked by legislation to the government.

In February 2019, the parliament of Belgium adopted a law establishing a permanent citizen assembly (called “Citizen Council") into the political landscape [2,3], reporting to the parliament. This model is considered unprecedented anywhere in the world [3]. This permanent organisation has 24 members who have previously participated in a time-limited citizen jury. Their tenure is for 18 months, with a third of the group being rotated at a time. The citizen assembly’s task is to set the agenda once each year, routinely follow up the parliamentary response to the citizen jury recommendations and to monitor preparations for upcoming citizen juries. Although they decide the topics to be considered by the citizen juries, they do not make recommendations themselves.

I believe Australian Primary Health Networks could realise multiple benefits by institutionalising permanent Citizen Assembly in each region. They would have deep relationship with a representative Council of community members, enabling immediate access to community insights. Secondly, the outcomes of Citizen Juries from time to time can inform and contribute to the Needs Assessment which is required by the Commonwealth. In that process, the need for external consultants would also reduce.

The sky is the limit!

References

1. Patriquin, L., Permanent citizens’ assemblies: A new model for public deliberation. 2019: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

2. Deutschsprachige Gemeinschaft. The Ostbelgien Model: a long-term Citizens' Council combined with short-term Citizens' Assemblies. 2019; Available from: https://oidp.net/en/practice.php?id=1237.

3. Niessen, C. and M. Reuchamps, Institutionalising citizen deliberation in parliament: The permanent citizens' dialogue in the German-speaking community of Belgium. Parliamentary affairs, 2022. 75(1): p. 135-153.

- Details

Primary Health Networks (PHNs) are mandated by the Australian government to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of health services for local populations, particularly those at risk of poor health outcomes. They are also mandated to improve the coordination of health services, and increase access and quality support for people in their local region [1]. They are entrusted with taxpayer funds to achieve this.

To deliver on this mandate it is imperative that local PHNs understand their local population of clinicians and communities to make sure that they know what services are working and what are not. The most frequently used vehicle to do this is to put together two groups using an expression of interest approach - a Clinical and a Community Council.

Council members tell us that a common error made by the health organisation is assuming that the purpose is to (mostly) give presentations informing members about the business of the PHN. In many cases, Councillors may not deeply understand that business - and may or may not be able to provide their input to make a difference. There are foundation stones missing and its hard to build on that. Its a bit like missing out on primary school and jumping into high school without the foundations.

We have found interesting ways to work towards realising the talent lying within your Councils. We evolved two Councils over a two year period and found that Councillors were able to contribute significantly to the business of the PHN, and enjoyed the experience, feeling a sense of commitment and connection to the PHN. The staff knew they were part of a joyful and rich process that delivered. We don't have to continue doing things that don't deliver a great outcome for everyone.

1. Australian Government. What Primary Health Networks are. 2021 [cited 2023 13 January]; Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/phn/what-PHNs-are.

2. World Health Organisation. Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- Details

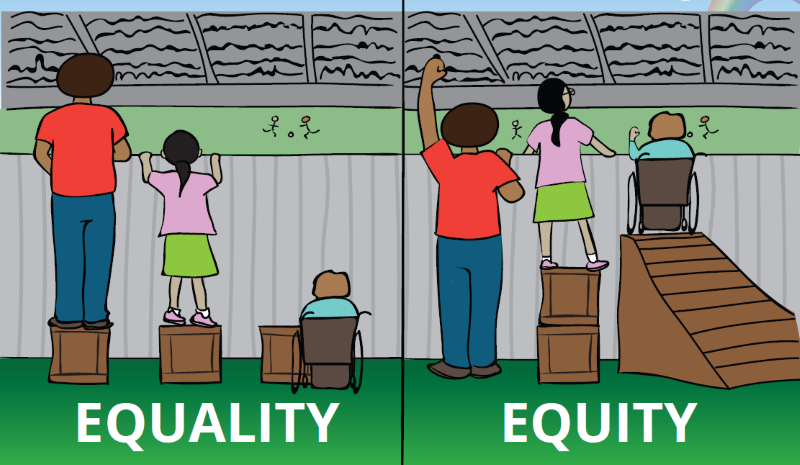

Equity is when all people are able to access what they need to be safe, healthy, and to thrive. It doesnt happen automatically. We as a community are responsible for taking action to level the playing field.

To create an equitable and healthy population we need to make sure that people can not only access healthcare, but also the social care that you have to have to be healthy.

Equity is not the same as equality.

Equality is when you offer the same thing to everybody. Problem with that is that some people aren't able to access what is offered to everybody. Think about a set of stairs if you are in a wheelchair.

Equality is when you offer the same thing to everybody. Problem with that is that some people aren't able to access what is offered to everybody. Think about a set of stairs if you are in a wheelchair.

You might be cured of cancer, but if you don't have a roof over your head its hard to survive.

You might be interested in hearing more. How does Climate change, health system transformation and health equity link up?

Oxford Comment podcast: Equity in Health Care Episode 74

Dr Jon Rhode talkes about what we need to do globally to improve health equity, then Dr Don Dizon, Director of the pelvic malignancies program and Lifespan Cancer Institute at Brown Uniersity talks about inequities in cancer care, highlighting the plight of gender and sexuality diverse people.

https://blog.oup.com/2022/07/equity-in-health-care-podcast/